In the shadow of global conflict and technological revolution, the 1940s quietly laid the groundwork for what would become a multi-billion dollar industry. While the world grappled with the aftermath of World War II, a handful of visionaries were tinkering with machines that would evolve into the immersive digital experiences we know today.

The 40s: Sparks in the Shadows of War

“Wait, This Math Puzzle Counts as a Game?“

Imagine being handed a mechanical contraption in 1940 that required you to strategically remove objects from piles. Nim, the first digital game ever created, wasn’t exactly Call of Duty. Played at the New York World’s Fair on a hulking machine, it appealed more to mathematicians than thrill-seekers.

Source : timetoast.com

For early gamers, this was less about escapism and more about marveling at technology’s potential—a novelty act in an age where “interactivity” meant pressing a button and watching gears clank.

Cathode Rays Meet Cold War Innovation

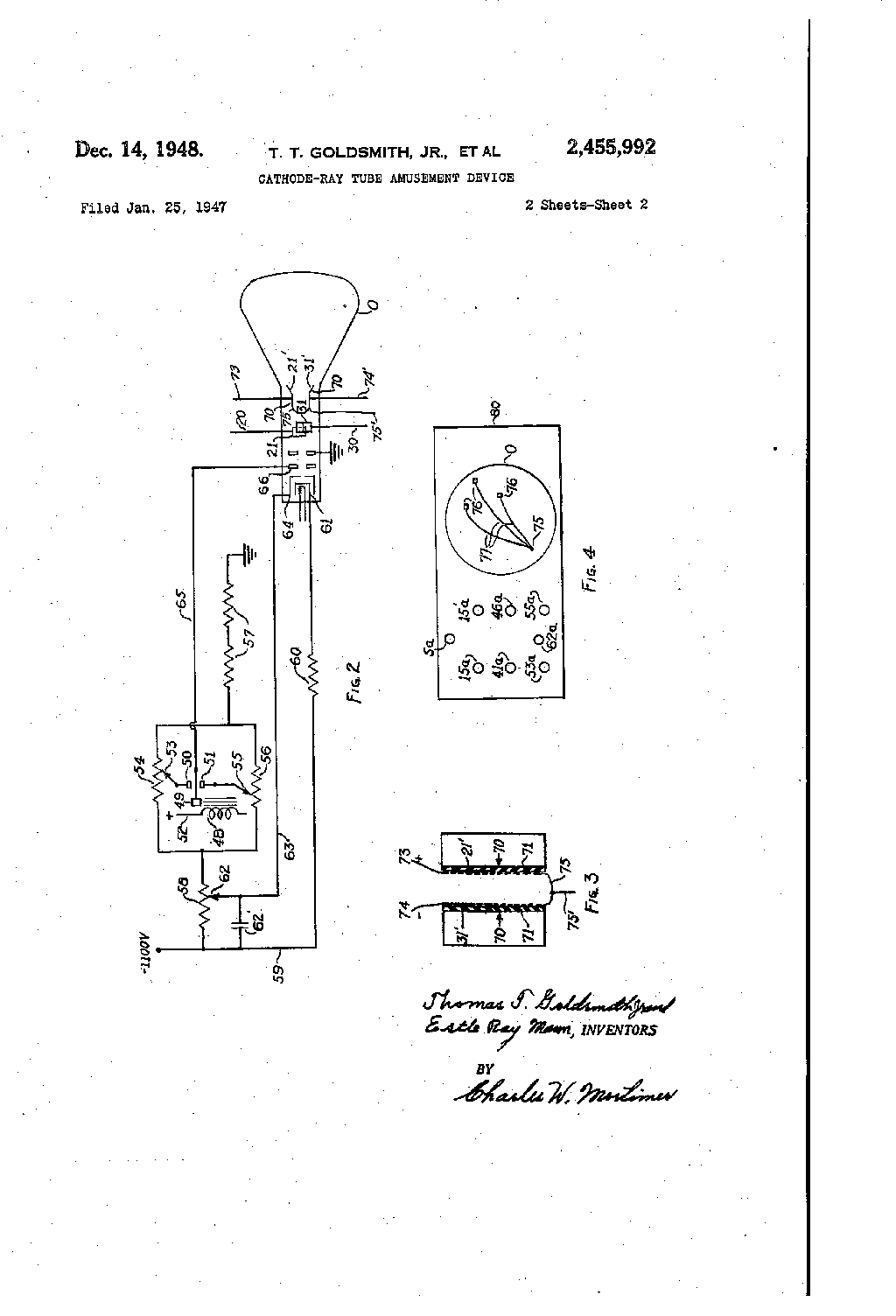

Behind the scenes, the 1940s birthed two foundational technologies. In 1947, Thomas Goldsmith and Estle Ray Mann patented the Cathode Ray Tube Amusement Device, a missile-defense simulator using analog circuits and CRT displays.

Source : historyofinformation.com

Though never commercialized, its blend of screen-based interaction and hardware hacking set a blueprint. Meanwhile, Nim leveraged relay circuits to automate combinatorial logic, proving computers could be repurposed for play. For engineers, these weren’t “games” but proofs-of-concept—toys that demonstrated computational flexibility during a time when computers were room-sized tools for artillery calculations.

No Market, No Problem

From a commercial standpoint, the 1940s were a desert. Nim and the CRT Amusement Device existed as curiosities, not products. With computers costing millions and CRT tech in its infancy, no sane entrepreneur would’ve invested in “video games.” Yet these experiments planted seeds: Goldsmith’s patent (assigned to DuMont Labs) hinted at corporate interest in entertainment applications, even if the timing was decades premature.

Final thoughts

The 1940s may seem like an unlikely birthplace for video games, but it was in this decade that the first sparks of digital entertainment were ignited. From the mathematical puzzles of Nim to the analog simulations of missile defense, these early experiments laid the foundation for an industry that would captivate generations to come.

Sources : timetoast.com – historyofinformation.com